Proving or disproving that an email of interest was received by the intended recipient is a request I received countless times throughout my digital forensics career. The request often goes as follows: “My opponent produced an email they claim to have sent me. I want to prove I never received this email.” Or, occasionally, it is the reverse: “I sent an email to my opponent, and they claim that they never received it. How can I prove that they did receive my email?“

In this article, I aim to discuss what the evidence can reveal when we review the sender’s copy of an email, how one can further investigate if the email was received, and what senders can do proactively to position themselves so that they are prepared to prove receipt of an email they send.

Sender’s Copy of The Email — Printout

Let’s start with a scenario where all that is available to us is a printout or screenshot of the sender’s copy of the email. What can this tell us, and how can it be authenticated?

Skip to PDF contentThe printout displays the message body and standard email metadata, including the sender, recipient, subject, attachment names, and origination date (although without the time zone and with only minute precision). One may examine such a printout and potentially determine the following:

- What email client was used to print the email

- If the printout was prepared from an electronic copy of the email (can help us surmise if a native or near-native copy of the email was available to the producing party at the time the printout was prepared)

- If the printout was modified after the email had been printed (e.g., by editing a PDF)

- If there are any apparent timing or time zone discrepancies

- If the signature blocks and company-wide disclaimers, if any, are where they should be

- What font was used in the email, if there are any timing issues related to the use of that font, and if there are any font, font size, or font color discrepancies within the email that would suggest copy / paste or modification

- If any stylistic patterns in the email body could help identify the author

And more.

In short, while far from ideal, an email printout is not useless by any means. That said, it would be challenging to authenticate an email based on a printout alone conclusively. At best, the investigator can examine the email for red flags. The lack of red flags does not guarantee authenticity.

What is often more important is what the email printout does not show us. I will cover this in the next section. As Craig Ball once wrote about converting an electronic document to an image format:

“It’s like photographing a steak. You can see it, but you can’t smell, taste or touch it; you can’t hear the sizzle, and you surely can’t eat it.“

This apt description also applies here. We can see what the email looks like, but we cannot see the email’s structure or many key metadata fields.

Sender’s Copy of The Email — Electronic MIME Message

What if, instead of a printout, we had an electronic version of the sender’s copy of the message in MIME format? What can we glean from an electronic copy that we were missing with the printout? As it turns out, a lot.

Return-Path: <ornatdilwen@gmail.com>

Received: from DESKTOPOI5E6B6 ([169.150.218.87])

by smtp.gmail.com with ESMTPSA id gs19-20020a170906f19300b00992f81122e1sm2947754ejb.21.2023.07.19.16.23.10

for <fecdev@yahoo.com>

(version=TLS1_2 cipher=ECDHE-ECDSA-AES128-GCM-SHA256 bits=128/128);

Wed, 19 Jul 2023 16:23:11 -0700 (PDT)

From: "Ornat Dilwen" <ornatdilwen@gmail.com>

To: <fecdev@yahoo.com>

Subject: Upcoming Project

Date: Wed, 19 Jul 2023 16:23:07 -0700

Organization: Tekoa Damyun, LLC

Message-ID: <015301d9ba97$fb561110$f2023330$@gmail.com>

MIME-Version: 1.0

Content-Type: multipart/mixed;

boundary="----=_NextPart_000_0154_01D9BA5D.4EF73910"

X-Mailer: Microsoft Outlook 14.0

Thread-Index: Adm6l7GMpPw44vDsSjOFgADxIFhLeA==

Content-Language: en-us

This is a multipart message in MIME format.

------=_NextPart_000_0154_01D9BA5D.4EF73910

Content-Type: multipart/related;

boundary="----=_NextPart_001_0155_01D9BA5D.4EF73910"

------=_NextPart_001_0155_01D9BA5D.4EF73910

Content-Type: multipart/alternative;

boundary="----=_NextPart_002_0156_01D9BA5D.4EF73910"

------=_NextPart_002_0156_01D9BA5D.4EF73910

Content-Type: text/plain;

charset="us-ascii"

Content-Transfer-Encoding: 7bit

Hello,

After carefully considering your requirements and objectives, our team has

formulated a comprehensive plan that aligns with your vision. I have

attached the detailed financial analysis outlining the scope, timeline, and

cost estimates for your review.

We are confident that our expertise and tailored approach will result in a

successful partnership. Should you have any questions or require further

information, please do not hesitate to reach out. We look forward to the

opportunity to work together and bring this project to fruition.

Ornat Dilwen

Tekoa Damyun, LLC

Description: tdamyun

------=_NextPart_002_0156_01D9BA5D.4EF73910

Content-Type: text/html;

charset="us-ascii"

Content-Transfer-Encoding: quoted-printable

<html xmlns:v=3D"urn:schemas-microsoft-com:vml" =

xmlns:o=3D"urn:schemas-microsoft-com:office:office" =

xmlns:w=3D"urn:schemas-microsoft-com:office:word" =

xmlns:m=3D"http://schemas.microsoft.com/office/2004/12/omml" =

xmlns=3D"http://www.w3.org/TR/REC-html40"><head><META =

HTTP-EQUIV=3D"Content-Type" CONTENT=3D"text/html; =

charset=3Dus-ascii"><meta name=3DGenerator content=3D"Microsoft Word 14 =

(filtered medium)"><!--[if !mso]><style>v\:* =

{behavior:url(#default#VML);}

o\:* {behavior:url(#default#VML);}

w\:* {behavior:url(#default#VML);}

.shape {behavior:url(#default#VML);}

</style><![endif]--><style><!--

/* Font Definitions */

@font-face

{font-family:Calibri;

panose-1:2 15 5 2 2 2 4 3 2 4;}

@font-face

{font-family:Tahoma;

panose-1:2 11 6 4 3 5 4 4 2 4;}

@font-face

{font-family:Bahnschrift;

panose-1:2 11 5 2 4 2 4 2 2 3;}

/* Style Definitions */

p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal

{margin:0in;

margin-bottom:.0001pt;

font-size:11.0pt;

font-family:"Calibri","sans-serif";}

a:link, span.MsoHyperlink

{mso-style-priority:99;

color:blue;

text-decoration:underline;}

a:visited, span.MsoHyperlinkFollowed

{mso-style-priority:99;

color:purple;

text-decoration:underline;}

p.MsoAcetate, li.MsoAcetate, div.MsoAcetate

{mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-link:"Balloon Text Char";

margin:0in;

margin-bottom:.0001pt;

font-size:8.0pt;

font-family:"Tahoma","sans-serif";}

span.EmailStyle17

{mso-style-type:personal-compose;

font-family:"Calibri","sans-serif";

color:windowtext;}

span.BalloonTextChar

{mso-style-name:"Balloon Text Char";

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-link:"Balloon Text";

font-family:"Tahoma","sans-serif";}

.MsoChpDefault

{mso-style-type:export-only;

font-family:"Calibri","sans-serif";}

@page WordSection1

{size:8.5in 11.0in;

margin:1.0in 1.0in 1.0in 1.0in;}

div.WordSection1

{page:WordSection1;}

--></style><!--[if gte mso 9]><xml>

<o:shapedefaults v:ext=3D"edit" spidmax=3D"1026" />

</xml><![endif]--><!--[if gte mso 9]><xml>

<o:shapelayout v:ext=3D"edit">

<o:idmap v:ext=3D"edit" data=3D"1" />

</o:shapelayout></xml><![endif]--></head><body lang=3DEN-US link=3Dblue =

vlink=3Dpurple><div class=3DWordSection1><p =

class=3DMsoNormal>Hello,<o:p></o:p></p><p =

class=3DMsoNormal><o:p> </o:p></p><p class=3DMsoNormal>After =

carefully considering your requirements and objectives, our team has =

formulated a comprehensive plan that aligns with your vision. I have =

attached the detailed financial analysis outlining the scope, timeline, =

and cost estimates for your review. <o:p></o:p></p><p =

class=3DMsoNormal><o:p> </o:p></p><p class=3DMsoNormal>We are =

confident that our expertise and tailored approach will result in a =

successful partnership. Should you have any questions or require further =

information, please do not hesitate to reach out. We look forward to the =

opportunity to work together and bring this project to =

fruition.<o:p></o:p></p><p class=3DMsoNormal><o:p> </o:p></p><p =

class=3DMsoNormal><span =

style=3D'font-family:"Bahnschrift","sans-serif"'>Ornat =

Dilwen<o:p></o:p></span></p><p class=3DMsoNormal><b><span =

style=3D'font-family:"Bahnschrift","sans-serif"'>Tekoa Damyun, =

LLC<o:p></o:p></span></b></p><p =

class=3DMsoNormal><o:p> </o:p></p><p class=3DMsoNormal><img =

width=3D412 height=3D202 id=3D"Picture_x0020_1" =

src=3D"cid:image001.png@01D9BA5D.4D6B9000" alt=3D"Description: =

tdamyun"><o:p></o:p></p><p class=3DMsoNormal><o:p> </o:p></p><p =

class=3DMsoNormal><o:p> </o:p></p></div></body></html>

------=_NextPart_002_0156_01D9BA5D.4EF73910--

------=_NextPart_001_0155_01D9BA5D.4EF73910

Content-Type: image/png;

name="image001.png"

Content-Transfer-Encoding: base64

Content-ID: <image001.png@01D9BA5D.4D6B9000>

<Base64 image contents omitted for brevity>

------=_NextPart_001_0155_01D9BA5D.4EF73910--

------=_NextPart_000_0154_01D9BA5D.4EF73910

Content-Type: application/x-zip-compressed;

name="Financial_Analysis.zip"

Content-Transfer-Encoding: base64

Content-Disposition: attachment;

filename="Financial_Analysis.zip"

<Base64 attachment contents omitted for brevity>

------=_NextPart_000_0154_01D9BA5D.4EF73910--

Here is a super quick breakdown:

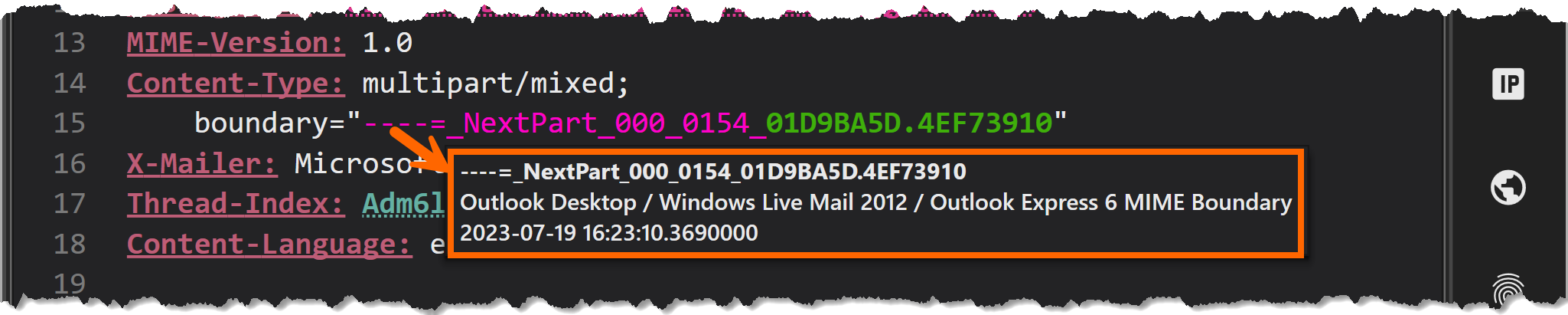

- We now have access to the MIME boundaries, which inform us about the email client that may have been used to compose the email. For this message, Outlook Desktop.

- In this case, the MIME boundaries have timestamps in FILETIME format (local time), which we can check against the apparent date of the email. The fact that these MIME boundary timestamps are in local time can also help us determine the sender’s time zone, if we did not already have that information.

- In some cases, one might observe nested MIME boundaries that could tip us off to modifications to the message. Not applicable to this message.

- We can check the HTML body of the email against the text body for any discrepancies.

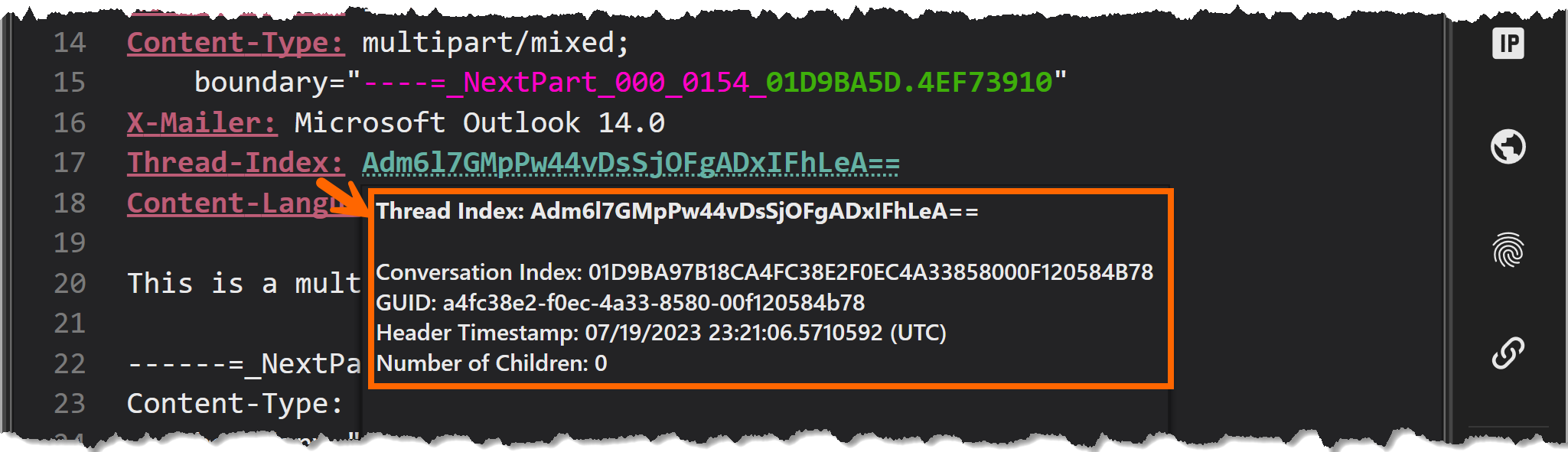

- We have a Thread-Index header, which gives us information about i) timing information regarding the creation of the message, ii) composition time, iii) GUID that could have been shared in other messages, iv) the skeleton of the email thread when child messages are present.

- We observe that the X-Mailer header points to Microsoft Outlook 14.0. Consistent with the MIME boundary.

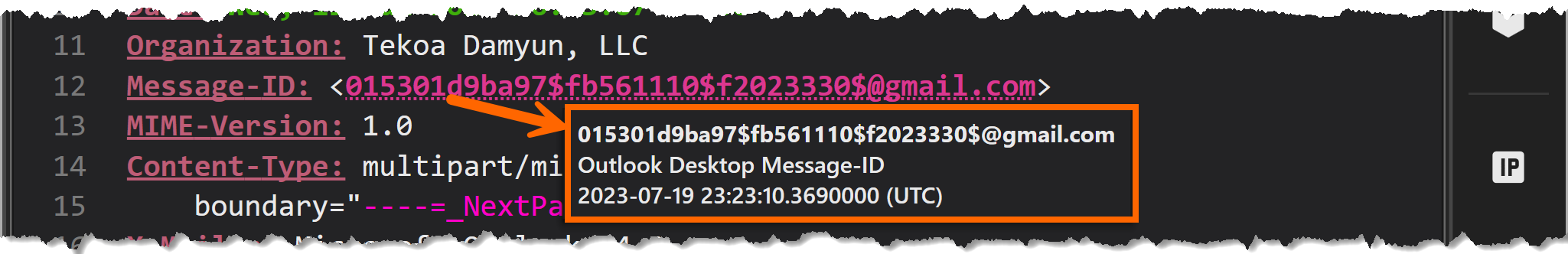

- We have access to the Message-ID, which is consistent with Outlook Desktop. This, too, gives us timing information in FILETIME format.

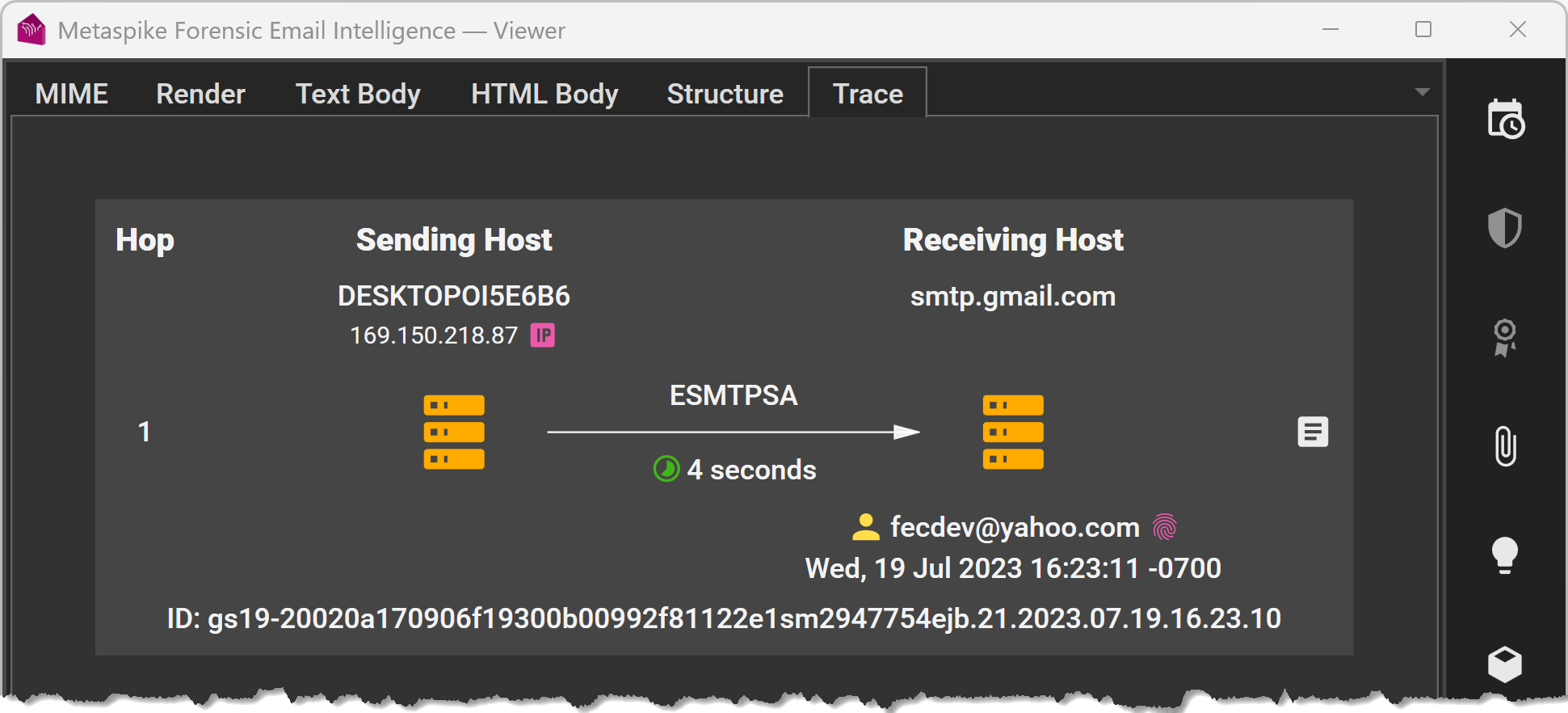

- We have a Received header that reflects the transmission from the local email client to the sender’s email server. This single-hop transmission, in this case, reflects the sender’s computer name, “DESKTOP-OI5E6B6,” and IP address (169.150.218.87). Nice!

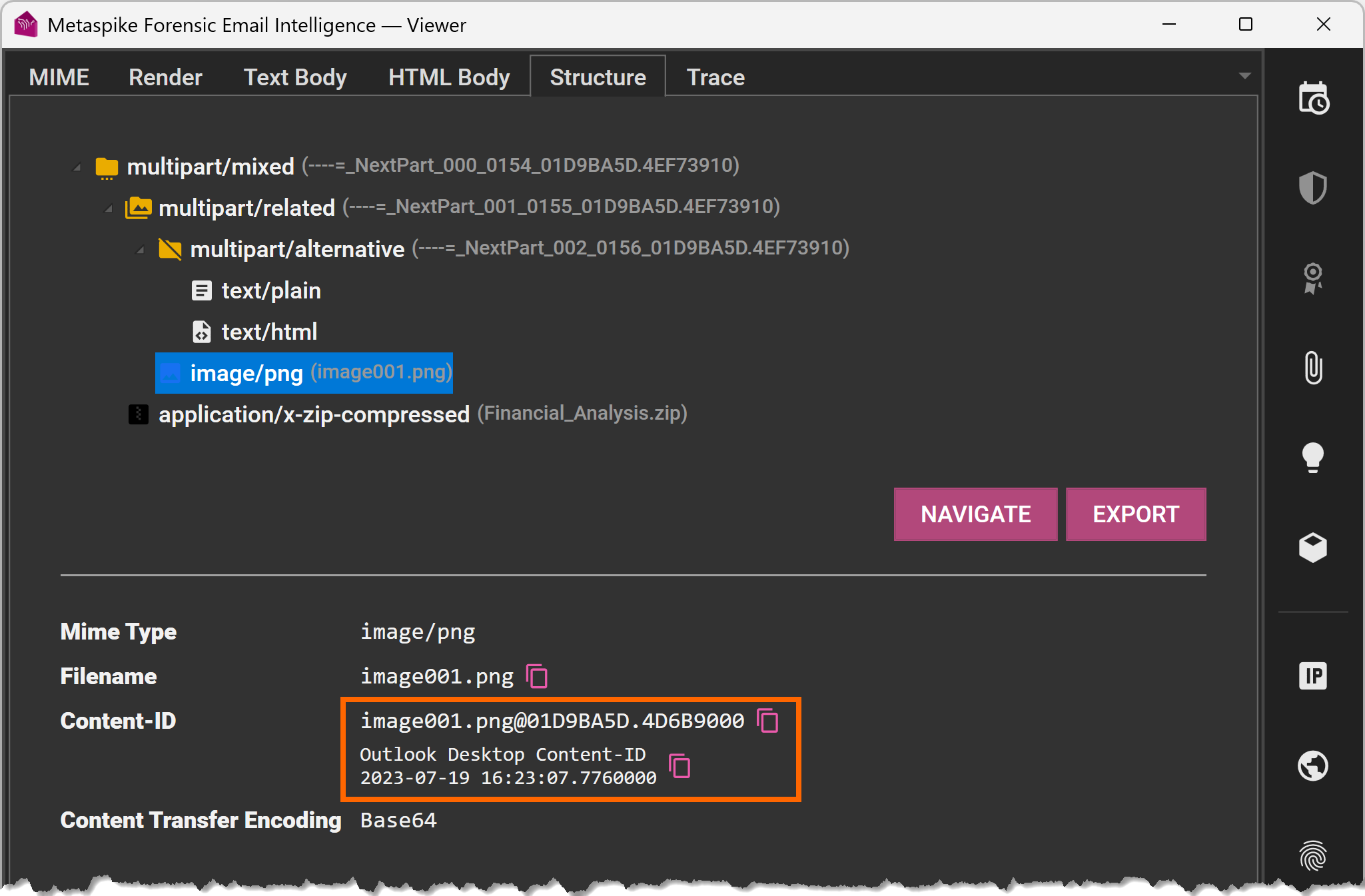

- We have access to a Content-ID value for the inline image. This is also consistent with Outlook Desktop and contains timing information in FILETIME format (local time).

- We can examine the message payload for any signs of modification, such as quoted-printable encoding issues.

- The HTML body of the message gives us clues about what software was used to compose the message. Again, consistent with Outlook Desktop.

- We can now see the origination date more clearly, with the time zone offset.

- We have access to the MIME structure of the message and can verify that it is compatible with that of a message with HTML and text bodies, an inline image attachment, and an external ZIP attachment (see above screenshot for Content-ID).

- We have access to the actual attachment of the email rather than only the name of the attachment seen in the printout. This allows us to authenticate the attachment as well and take any timing information within the attachment into account when validating the email.

And more!

We can put all this information to good use and increase our confidence in our analysis of the message. However, the sender’s copy of the message does not give us two important things:

- It does not include the trace information that reflects the travel of the message from the sender to the recipient.

- It does not contain the DomainKeys Identified Mail (DKIM) and Authenticated Received Chain (ARC) signatures one would expect to find in a message between Gmail and Yahoo in 2023. Those would be added to the message during transit.

Conclusions About The Sender’s Copy of the Message

Let’s summarize what the sender’s copy of the email gave us:

Printout: While the printout contains valuable information that can be used toward authentication, it is not in a reasonably usable format for forensic authentication.

MIME Copy: The MIME copy can be used to go much further in terms of authentication. But does it prove that the email was received? Not by a long shot. There is no transmission information, nor are there DKIM and ARC signatures. Even if the sender composed the message and intended to send it, there is nothing in the message that proves that the message was successfully delivered to the intended recipient’s mailbox. It is even challenging to determine conclusively that the sender sent the message, as it is feasible to create such a message after the fact—it is a text file with no digital signatures. We will discuss below how this can be overcome.

Taking Things A Step Further

Other Recipients

Let’s start with what is the lowest hanging fruit: if the email has other TO, CC, or BCC recipients, and if one or more of those recipients received the message and can produce a copy from their perspective, that adds further clarity.

This would still not prove that the message was successfully delivered to the mailbox of the recipient of interest, but it at least shows that the sender indeed composed and sent the message.

Server Metadata

Depending on the email system, there are numerous pieces of server metadata one can use. One of the options that is easy to illustrate is IMAP server metadata. We can use a combination of Unique Identifier (UID) and Internal Date Message Attributes, and the Unique Identifier Validity (UIDVALIDITY) value to increase our confidence in whether a message found on an IMAP server is likely to be authentic.

When investigating the sender’s copy of the message, we can use this information to confirm that the message of interest arrived at the “Sent Items” folder at a time compatible with the apparent origination date of the email rather than being planted there after the fact (see Forensic Examination of Manipulated Email in Gmail).

When investigating the receiver’s side, we can scan the recipient’s “Inbox” for the relevant time period to see if there are any UID gaps in the temporal neighborhood when the message would have been received. If the UIDs are gapless in the relevant area, that would increase our confidence that the message was not delivered to that mail folder (as opposed to being delivered and subsequently deleted).

In both cases, we would pay close attention to the UIDVALIDITY of the folder. For example, Yahoo uses Epoch timestamps with second precision as the UIDVALIDITY for folders. Timing information regarding the creation of the mail folder can help confirm whether the end-user could have nuked and recreated the entire folder after the fact to arrive at gapless UIDs.

References in Other Messages

Two unique identifiers in emails, the Message-ID header, and the Conversation Index GUID, can sometimes lead to interesting discoveries.

In our scenario, if the recipient of the email creates a new message by replying to or forwarding the email of interest, the Message-ID of the email would likely be reflected in the In-Reply-To and/or References headers of the newly-created message. Such linkage can be used to show that the recipient must have received the email of interest.

When present, Conversation Index can be used the same way. If a new email is created based on the email of interest, the Conversation Index header block will carry over, leading to similar conclusions.

Endpoint Forensics

In cases where we have access to the recipient’s devices (computers, cell phones, tablets, etc.), conventional endpoint forensics methods can be used to further our investigation.

Perhaps the first order of business would be to create a searchable index based on the forensic images of the endpoints and search for the email of interest. One can use relatively unique fragments of the body text, Message-ID, etc.

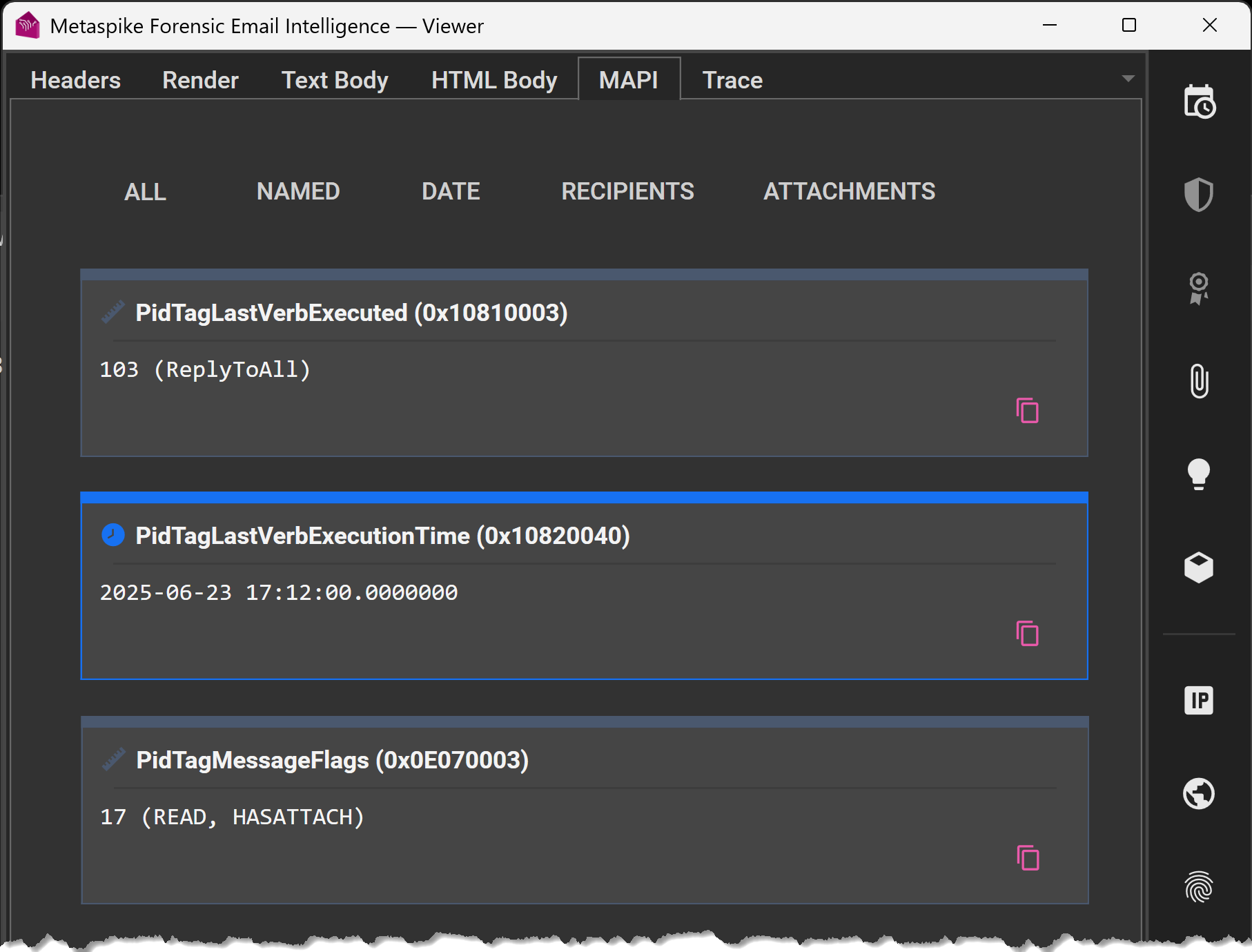

In some cases, local copies of the emails may have metadata beyond what is included in a typical MIME message. For example, if the endpoint contains a local cache of emails in a MAPI container (e.g., OST, PST), one can examine the MAPI properties to obtain information beyond the receipt of the email. The screenshot below shows a few MAPI properties that reflect the last verb executed on a message (reply to all), the timing of that action, and the message flags that show that the message was read and that it has attachments. Note that this is a minimal subset of what is available for examination—this test message contained over 200 MAPI properties.

Small Subset of MAPI Properties

If the email of interest has attachments, endpoints can be examined to discover any user interactions with the attachments. For instance, on a Windows system, one might review the event logs, LNK files, virus scan logs, Shell Bags, Jump Lists, Office File MRU & Place MRU, OpenSaveMRU & LastVisitedMRU, prefetch, browser history for local files, Windows Search Index, etc. If the recipient’s computer system shows signs of their having opened attachments of the email of interest, and if those attachments were not available to them through another source, that can be strong evidence that they received and opened the email.

Proactive Measures

What are some proactive measures senders can take to position themselves such that their sending of a vital email can later be verified relatively easily? I will divide these into two main categories:

Measures That Require Cooperation from the Recipient

You might say: “Wait a minute, why would the recipient cooperate if they are the opponent in a legal action?”. Well, in many cases, the recipient is not an opponent at the time the email was sent but perhaps a cooperative business partner, employer, contractor, etc. They may have very well cooperated at that stage before the relationship went south.

Ask the recipient to confirm receipt: Perhaps this goes without saying, but if you are sending an important email and ask the recipient to confirm receipt, they may very well do so. Assuming that your email provider employs DKIM and ARC signing (which will be discussed below), the confirmation message you receive could go a long way toward establishing that the email was received.

Request read and delivery receipts: Some email clients, such as Outlook, allow senders to request read and delivery receipts. While these are often overlooked by email systems and end-users, they can be helpful on occasion.

Tracking images and hyperlinks: It is possible to insert images or hyperlinks into outgoing emails to track the recipient’s interactions with the message. The images would require the end-user to allow downloading/displaying remote images. And the hyperlink option would require the recipient to click on the hyperlink.

When successfully used, these methods can not only confirm that the email was received but also provide additional details about the recipient’s IP address, device information, and more (example).

Independent Measures

Email provider that signs messages: Using a reputable email service provider that signs messages (i.e., DKIM and ARC) and that does not alter messages so that the signatures can be verified after receipt can be hugely beneficial. In a nutshell, the email provider signs the message body, attachments, and a selection of MIME headers using their private key. The signature can be verified using the public key of the provider, which can be obtained via a DNS request. This makes it relatively painless to show that the signed parts of the email could not have been modified by the end user after transmission.

How does this help in investigations concerning whether an email of interest was received? In many ways. For instance, if you are the recipient of the message, and the message that the sender claims that you received is not the same as what you received, you can verify the DKIM & ARC signatures of your copy of the message to show that yours is the authentic copy.

Another use case, this time for the sender, would be when the sender asks the recipient to confirm receipt of the email. When they do, the received confirmation can easily be authenticated if it contains verifiable DKIM and ARC signatures.

One more use case is as follows.

Maintain a separate filing mailbox: Another approach senders can take is to maintain a separate filing mailbox—ideally, hosted by a separate email provider—where they CC or BCC any important outgoing emails.

Assuming that the filing mailbox email provider properly signs incoming messages, this would help the sender establish two things: 1) the message that the sender claims to have sent was indeed composed when they said it was; 2) the sender actually sent the message, and it was delivered to an external mailbox.

For #2, it is essential that the filing mailbox email provider includes the participant headers (from, to, cc, bcc) in the DKIM calculation so that verifying DKIM & ARC confirms not only that the message was sent but also to whom it was sent.

DKIM & ARC public keys used by the filing mailbox email provider should be archived regularly to protect against future key unavailability. Some providers continue to use the same keys for several years, while others periodically decommission keys.

Again, this does not prove that the email of interest was successfully delivered to the mailbox of the intended recipient. But, in many cases, showing that the sender composed a specific message at a certain point in time and sent it to the recipient of interest can go a long way.

Summary & Conclusions

It can be quite a challenge for a sender to prove that the intended recipient received their email message. It can be equally, if not more, challenging for a recipient to prove that they did not receive an email.

Exchanging email evidence in native or near-native format alleviates some of the authentication challenges. An email printout or screenshot produced from the sender’s perspective does not prove that the email was successfully delivered to the recipient’s mailbox. That said, the sender’s copy of a message can be authenticated—especially if produced in native format, even more so if a DKIM-signed copy was received in a separate filing mailbox or by another recipient—to increase one’s confidence that the email was composed at the claimed time.

In addition to the sender’s copy, server metadata analysis (e.g., UID vs. Internal Date) can be used to show that a message found in the sender’s “Sent Items” folder is likely to be authentic, or that the recipient’s “Inbox” has no gaps that would have indicated that the message could have been received and subsequently deleted.

When additional emails are available from the recipient’s document productions, contextual analysis can be performed to determine whether any of the unique identifiers of the email of interest, such as Message-ID and Conversation Index GUID, appear in other emails. If they do, this would support the receiver’s having received the email.

Finally, in scenarios where forensic examiners have access to endpoint evidence, they can examine local caches of messages—including their MAPI properties, if available—and use conventional endpoint forensics methods to investigate user interactions with the email and its attachments.

References:

RFC 5322: Internet Message Format — https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc5322

RFC 3501: INTERNET MESSAGE ACCESS PROTOCOL – VERSION 4rev1 — https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc3501

RFC 2045: Multipurpose Internet Mail Extensions (MIME) Part One: Format of Internet Message Bodies — https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc2045

Are They Trying to Screw Me? — https://craigball.net/2012/10/09/are-they-trying-to-screw-me/

Arman Gungor is a certified computer forensic examiner (CCE) and software developer. He has been appointed by courts as a neutral computer forensics expert as well as a neutral eDiscovery consultant. Arman is passionate about doing digital forensics research, developing new investigative techniques, and creating software to support them.